Series

Exhibitions

Art and Architecture

Chromasonic

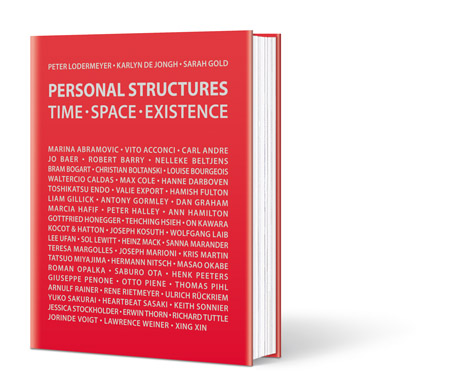

Texts / Catalogs / Books

-

Art & Architecture

-

-

Studio Harriet & Johannes Girardoni

-

-

Metaspaces

-

-

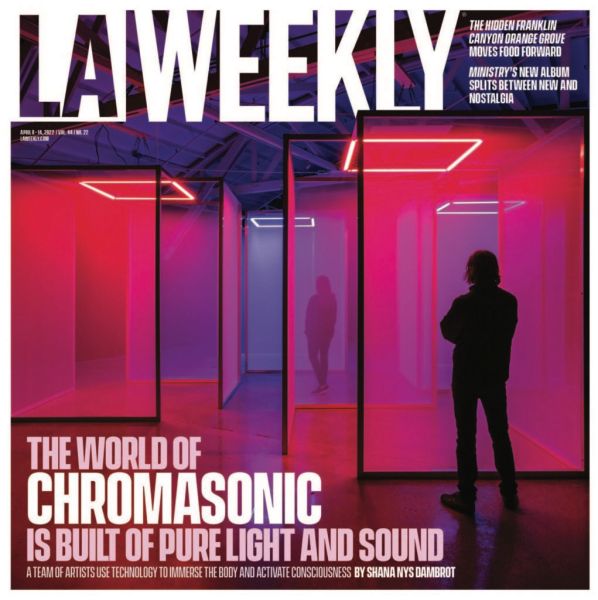

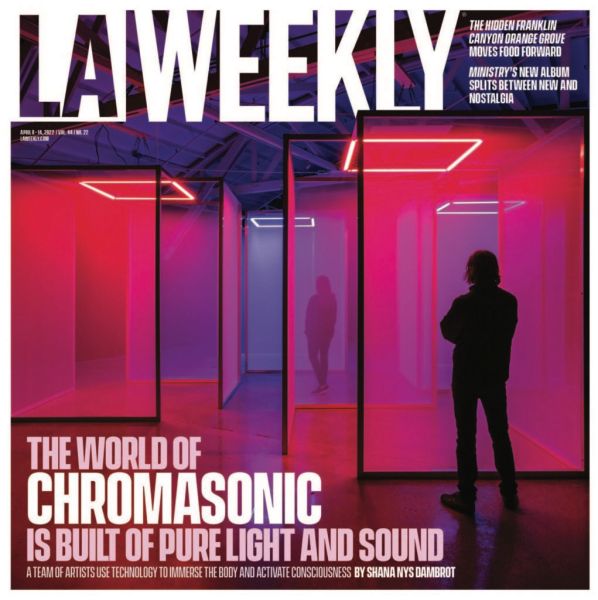

The World of Chromasonic is Built of Pure Light and Sound

-

-

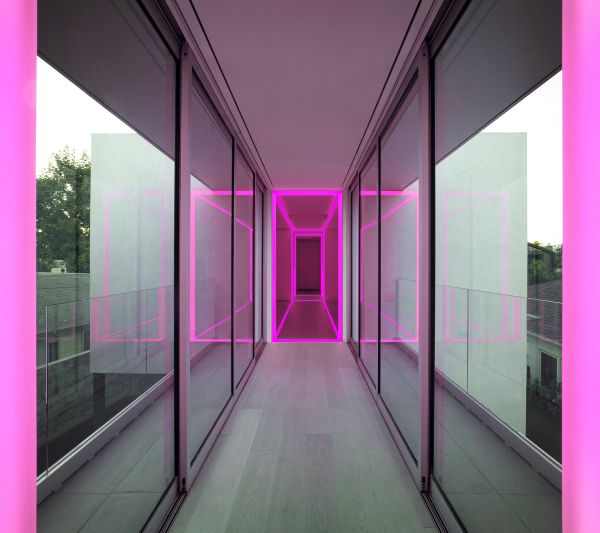

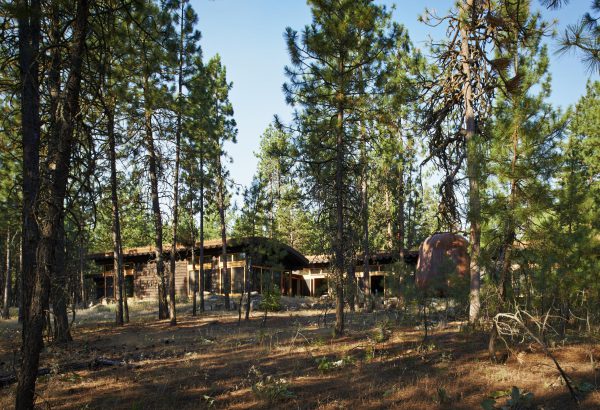

Spectral Bridge House: Blending Art+Architecture

-

-

Resonance; Richard Speer

-

-

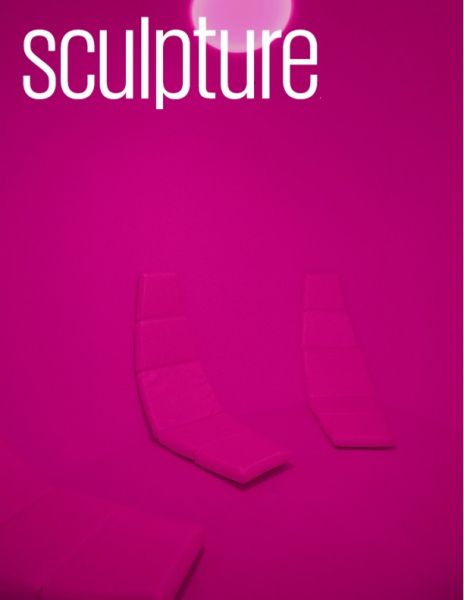

Off and On; Sculpture Magazine

-

-

In Conversation with Johannes Girardoni; Jeff Simpson

-

-

Off and On; Exhibition Catalog

-

Seeing, Outside Our Selves; Johannes Girardoni

-

-

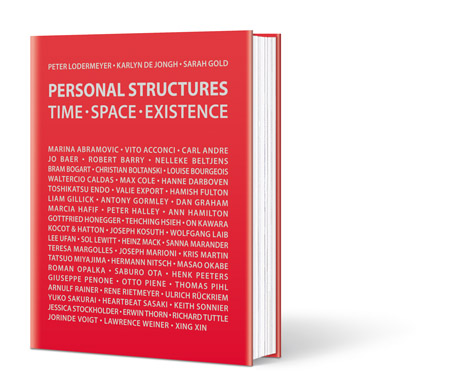

Personal Structures; Sculpture Magazine

-

-

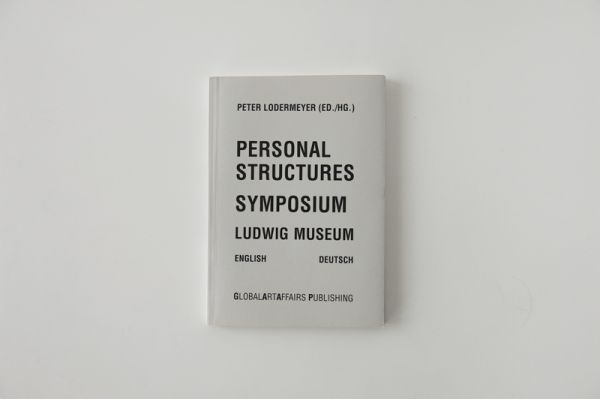

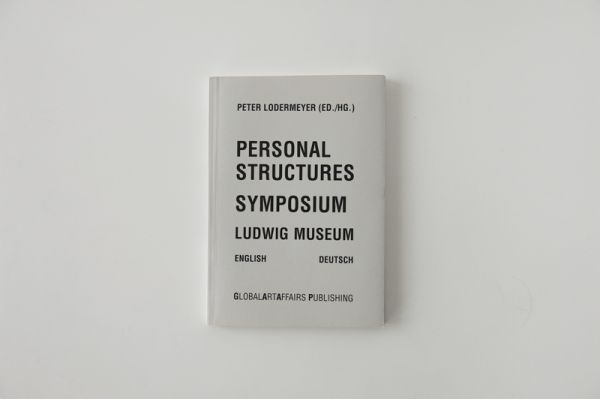

Ludwig Museum Symposium; Johannes Girardoni

-

-

-

Art & Architecture

-

-

Studio Harriet & Johannes Girardoni

-

-

Metaspaces

-

-

-

-

The World of Chromasonic is Built of Pure Light and Sound

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Spectral Bridge House: Blending Art+Architecture

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Resonance; Richard Speer

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Off and On; Sculpture Magazine

-

-

-

In Conversation with Johannes Girardoni; Jeff Simpson

-

-

Off and On; Exhibition Catalog

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Seeing, Outside Our Selves; Johannes Girardoni

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Personal Structures; Sculpture Magazine

-

-

-

-

-

Ludwig Museum Symposium; Johannes Girardoni

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Installations

-

2019

Spectral Bridgetest

-

2017

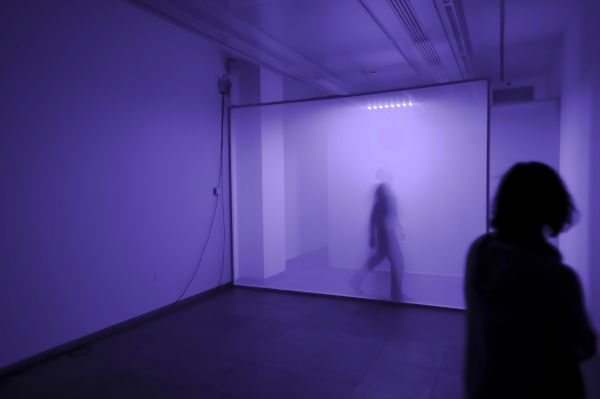

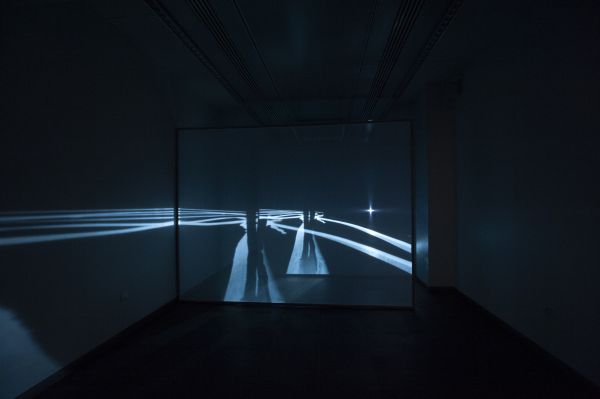

Resonancetest

-

2013

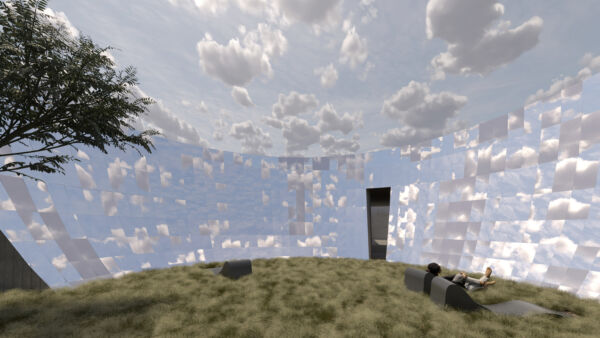

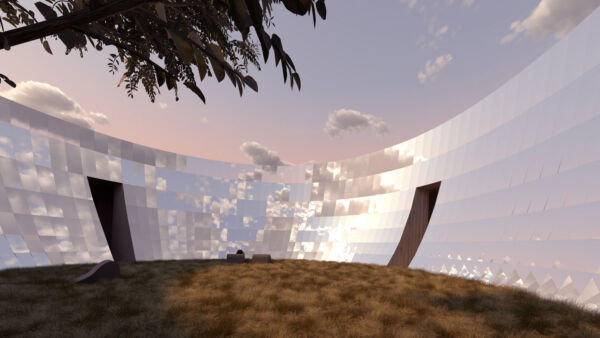

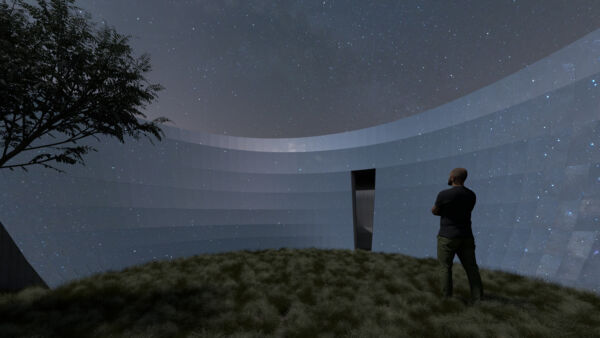

Metaspace V2

- Metaspace V2 (exterior)

- Metaspace V2 (interior)

- Metaspace V2 (projection)

-

2013

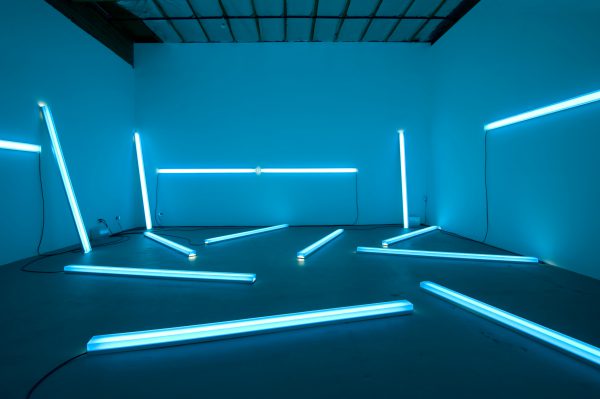

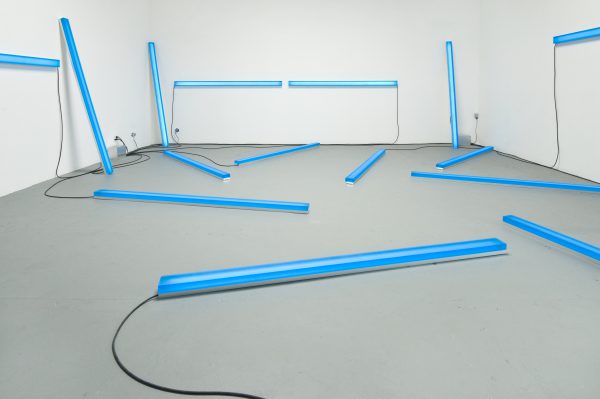

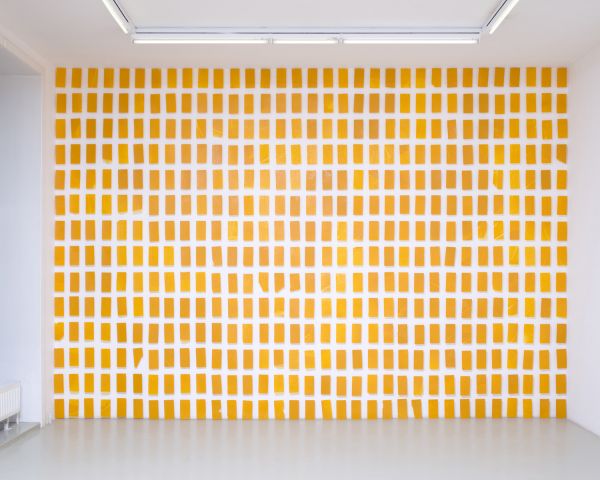

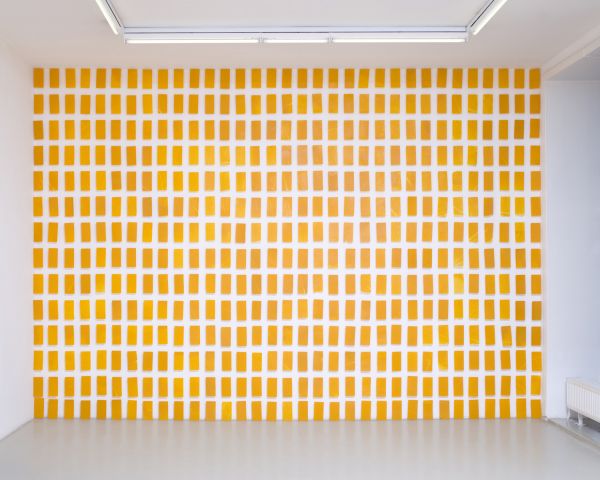

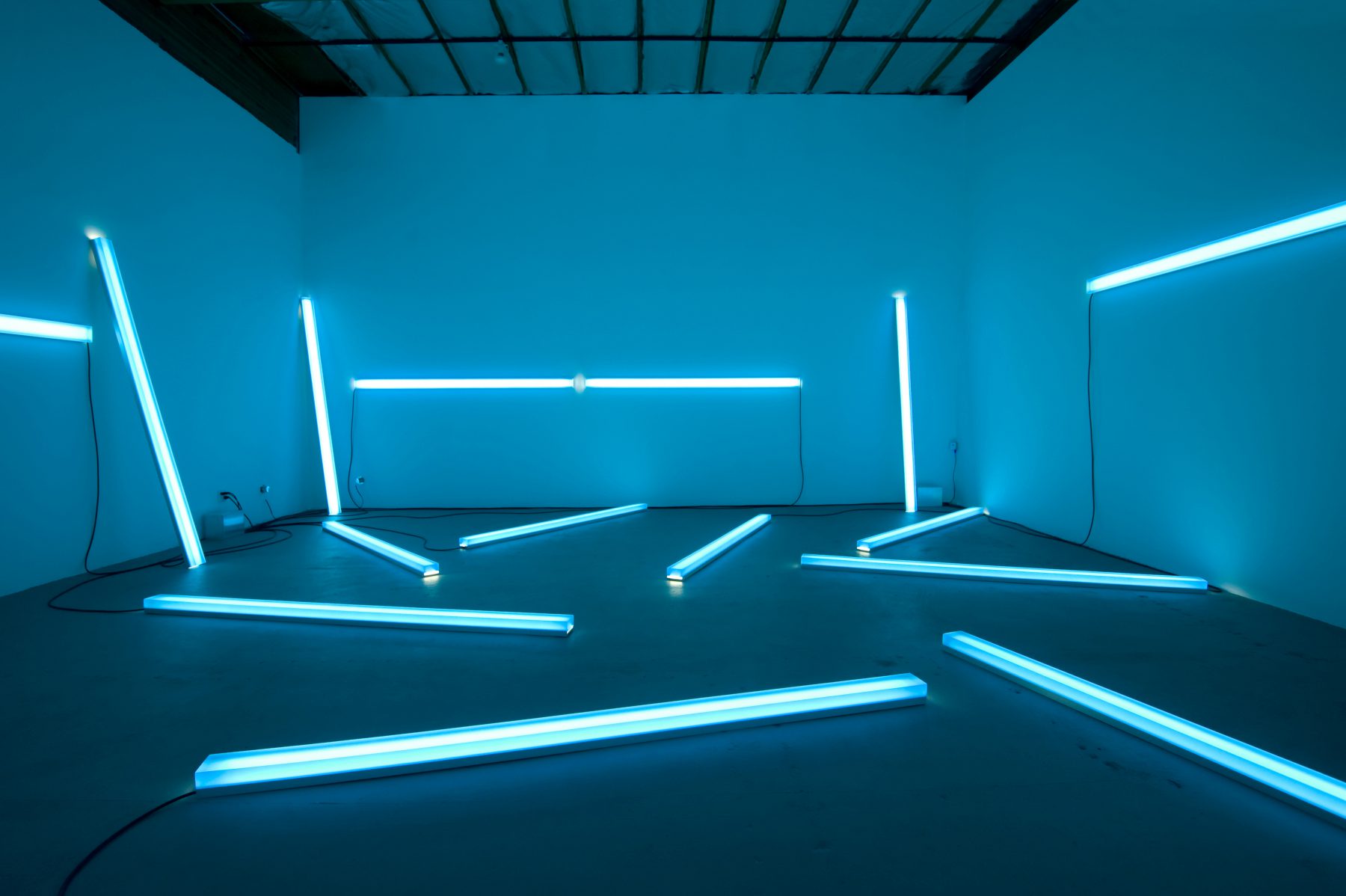

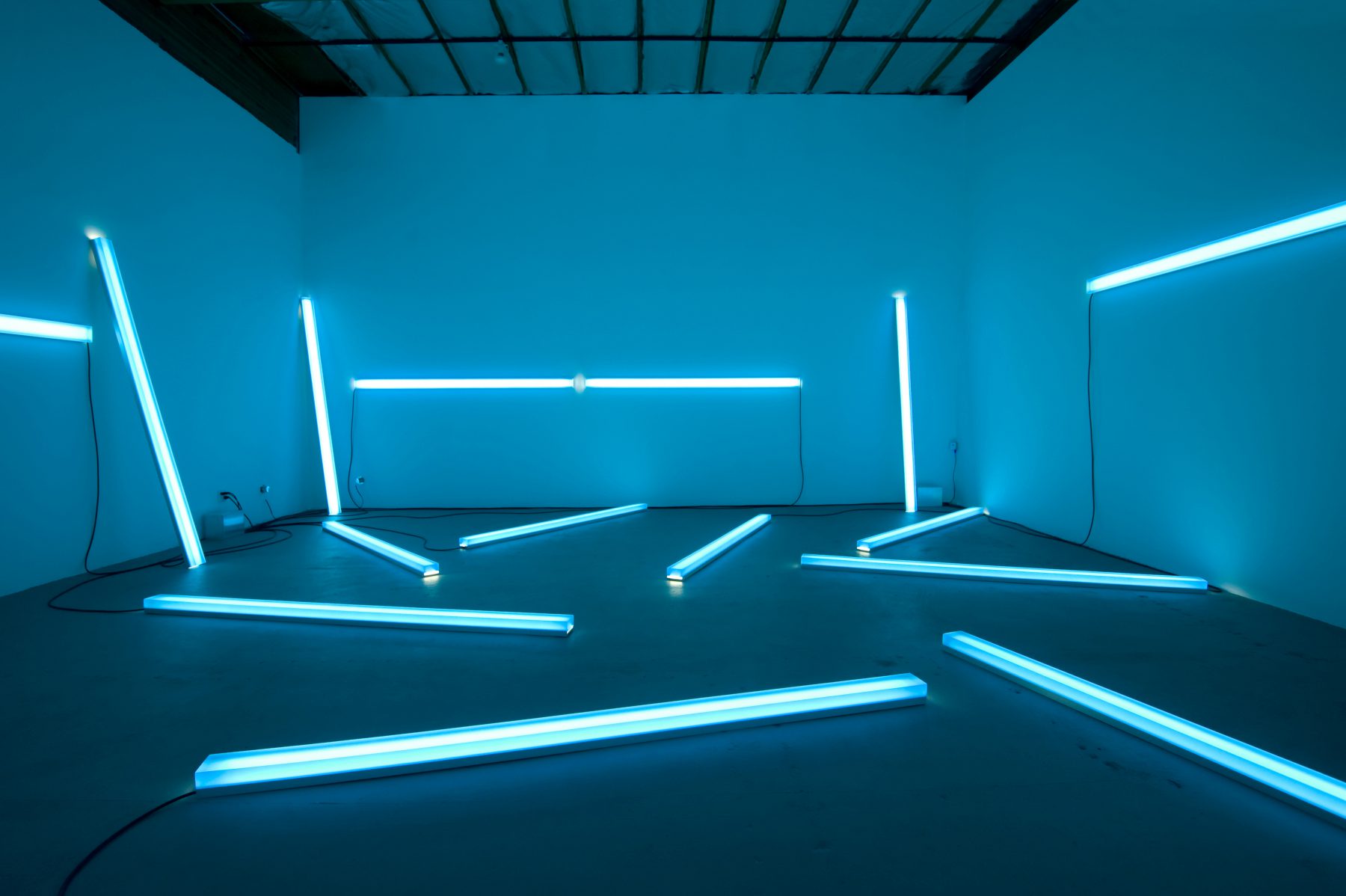

Chromasonic Field — Blue / Greentest

-

2012

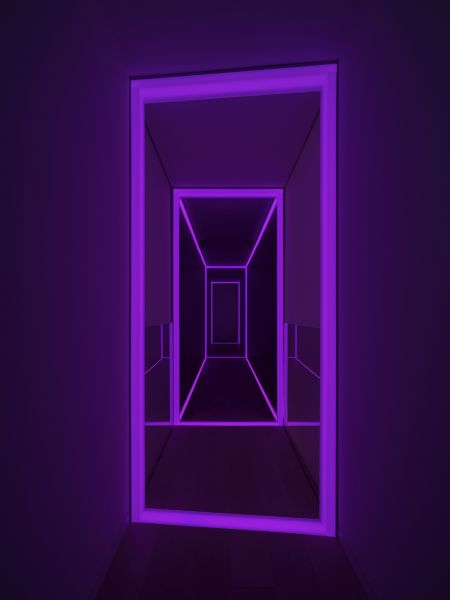

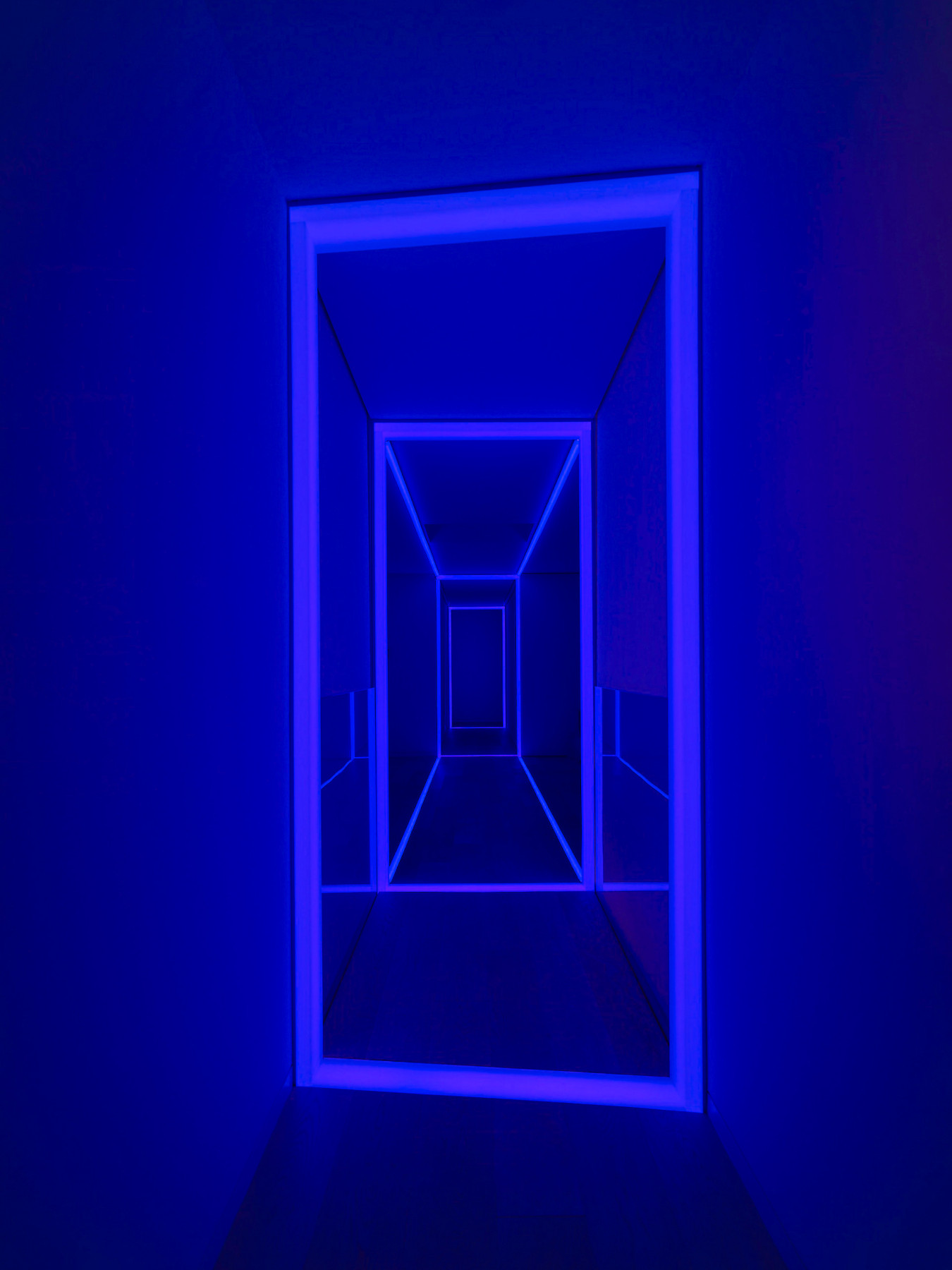

The Infinite Room (Metaspace 1)test

-

2011

The (Dis)appearance of Everythingtest

-

2009

The Passage Roomtest

-

2008

In Front of the Plane Nr. 6test

-

2004

reVIBRATION No. 01 (rV01)test

-

2004

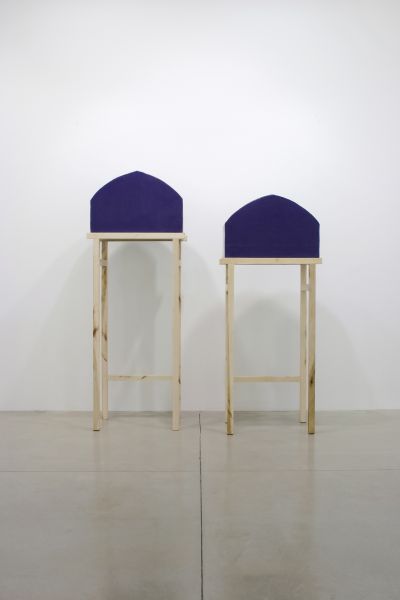

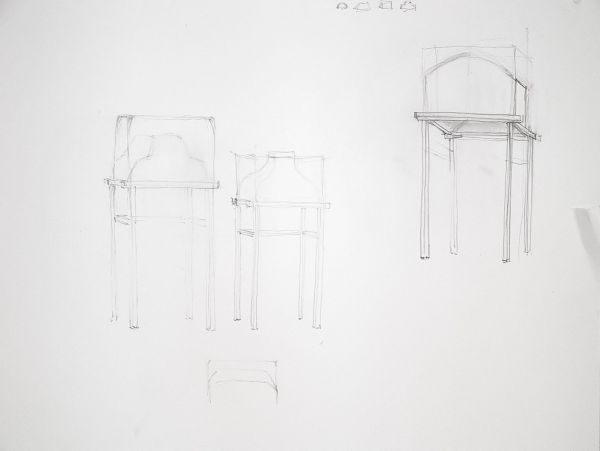

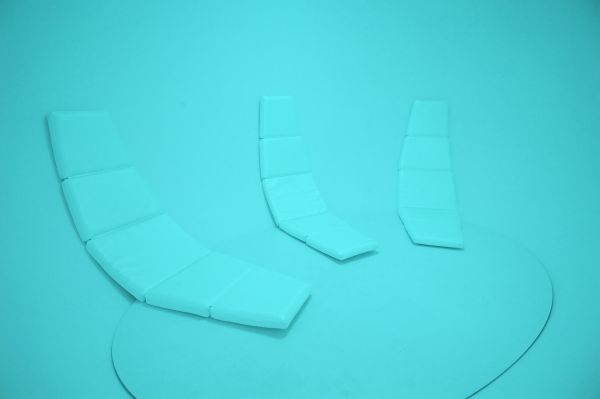

MonoPodstest

-

1995

Stacked.3600 (Sound of Silence)test

Series

-

2018

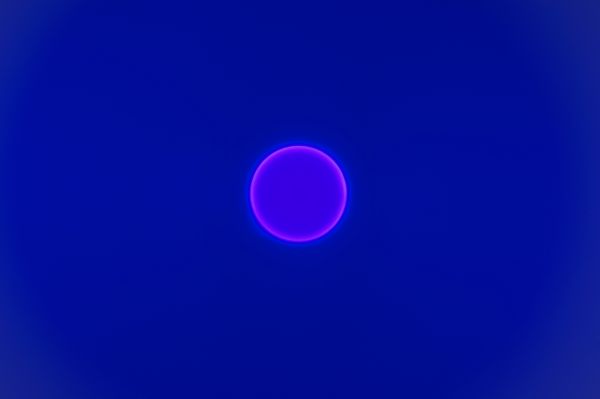

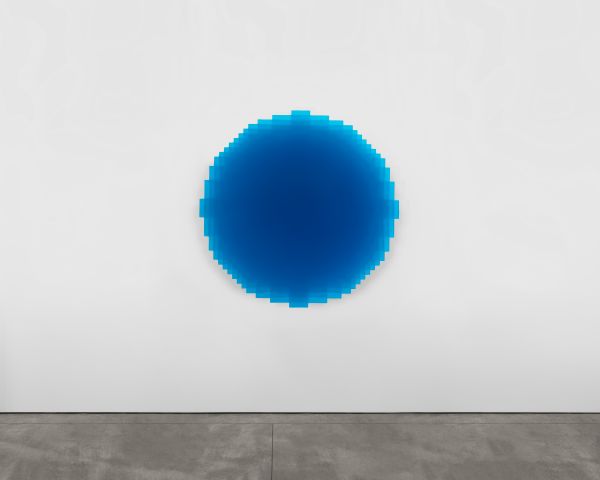

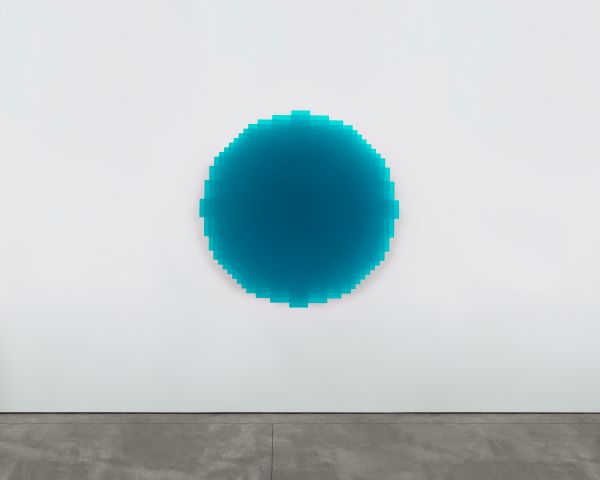

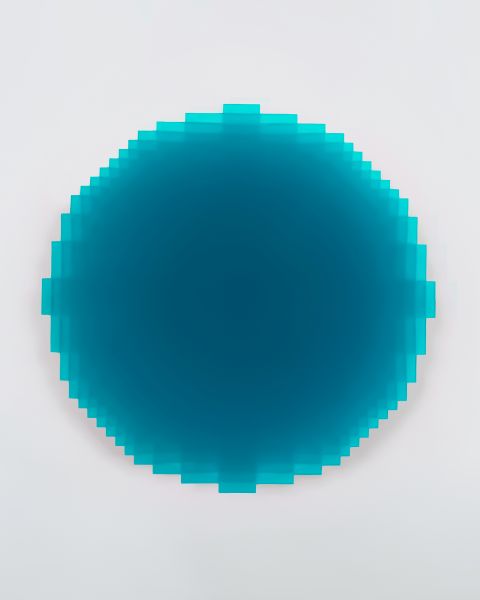

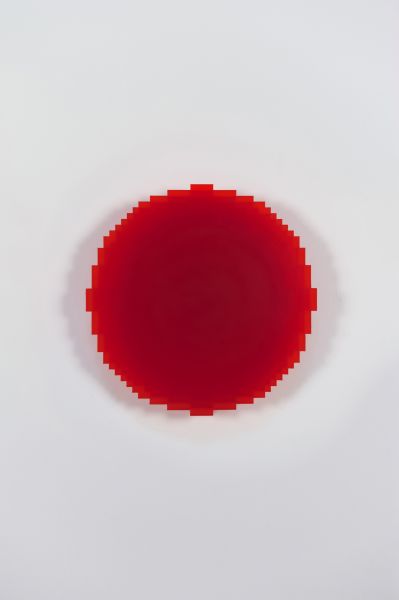

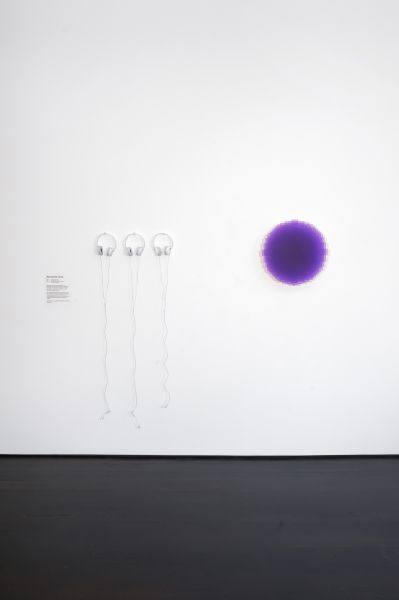

Resonant Disks

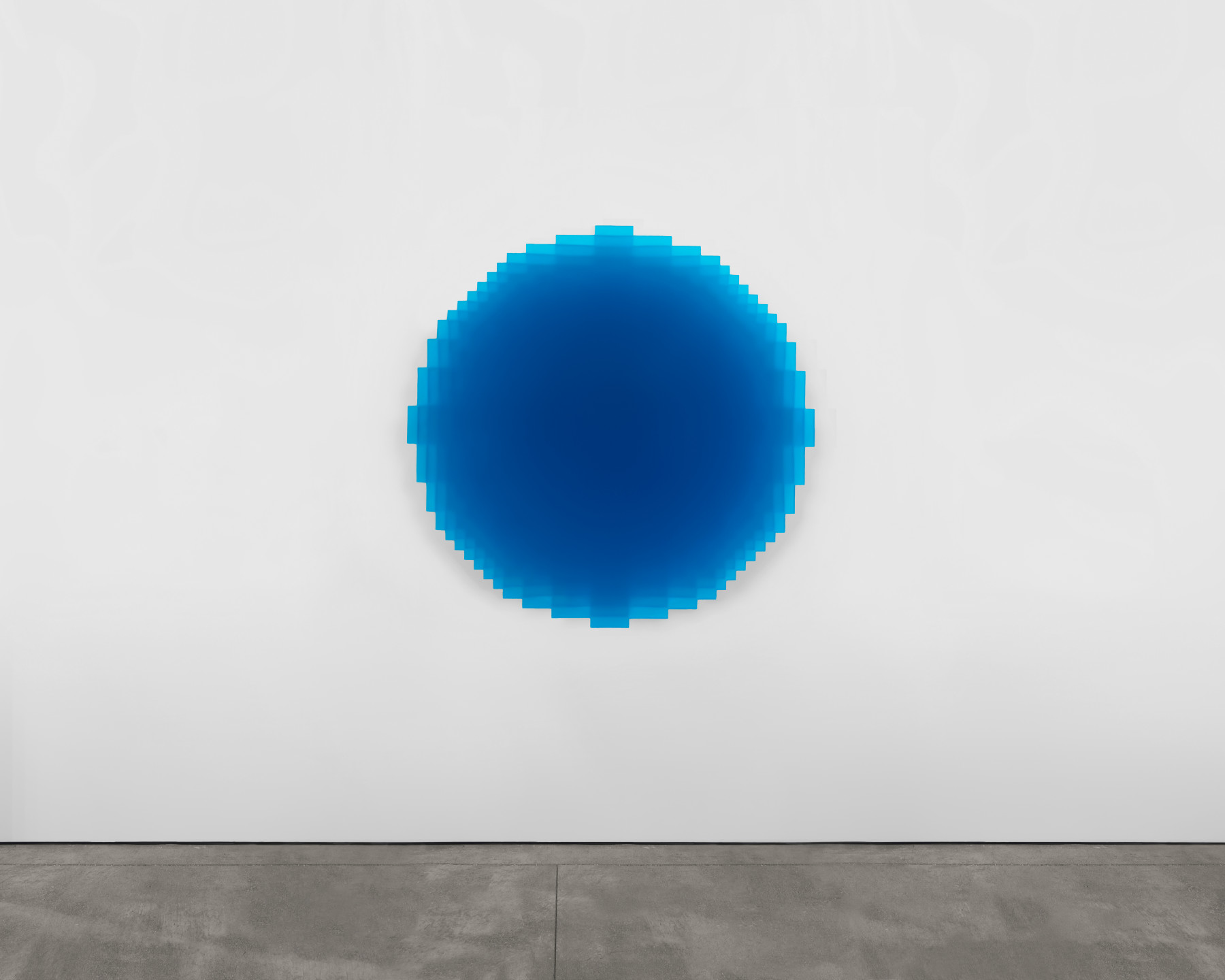

- Resonant Disk – Blue Green

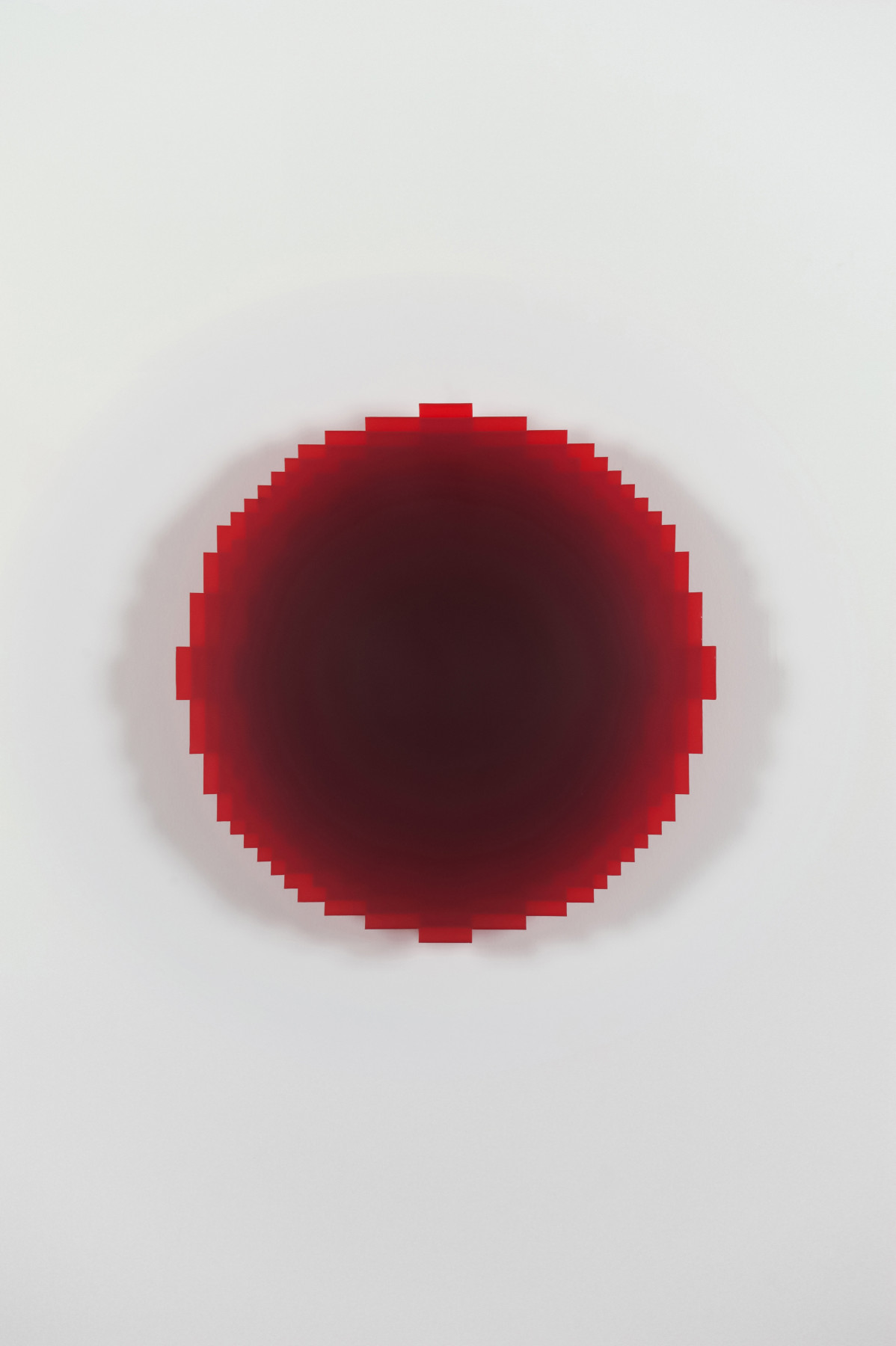

- Resonant Disk – Red Violet

- Resonant Disk — Yellow Blue

-

2011–2025

Refrequenced Sculpture

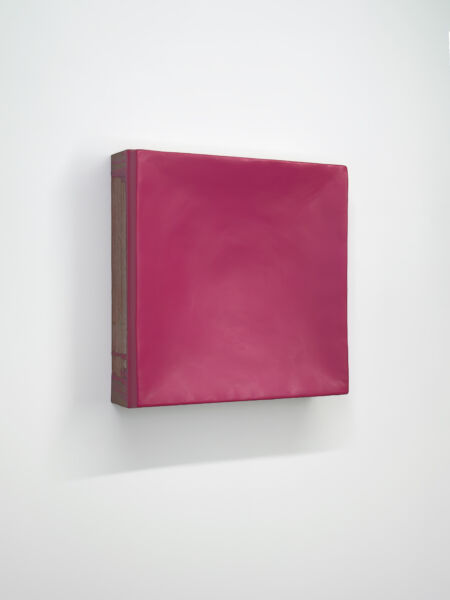

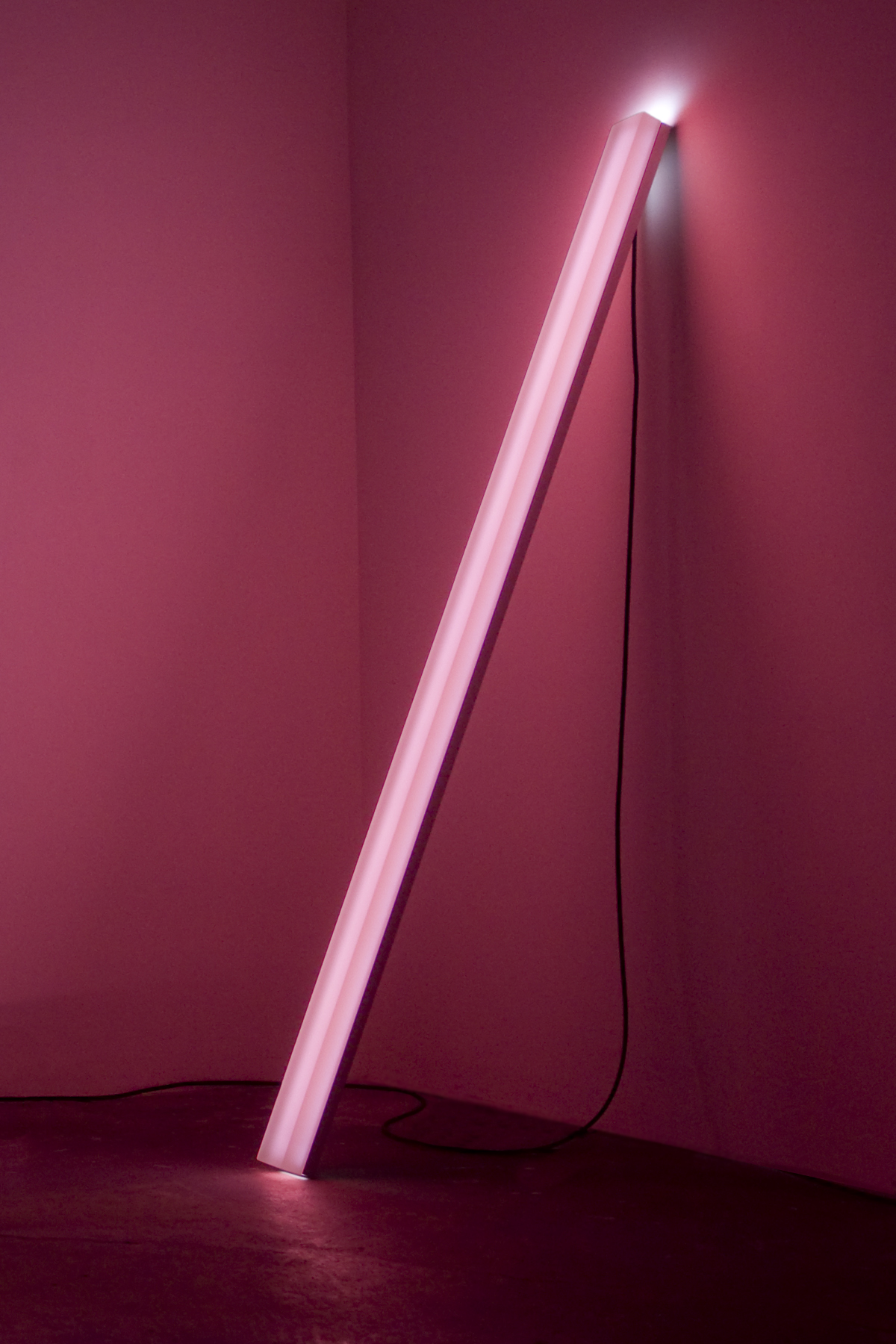

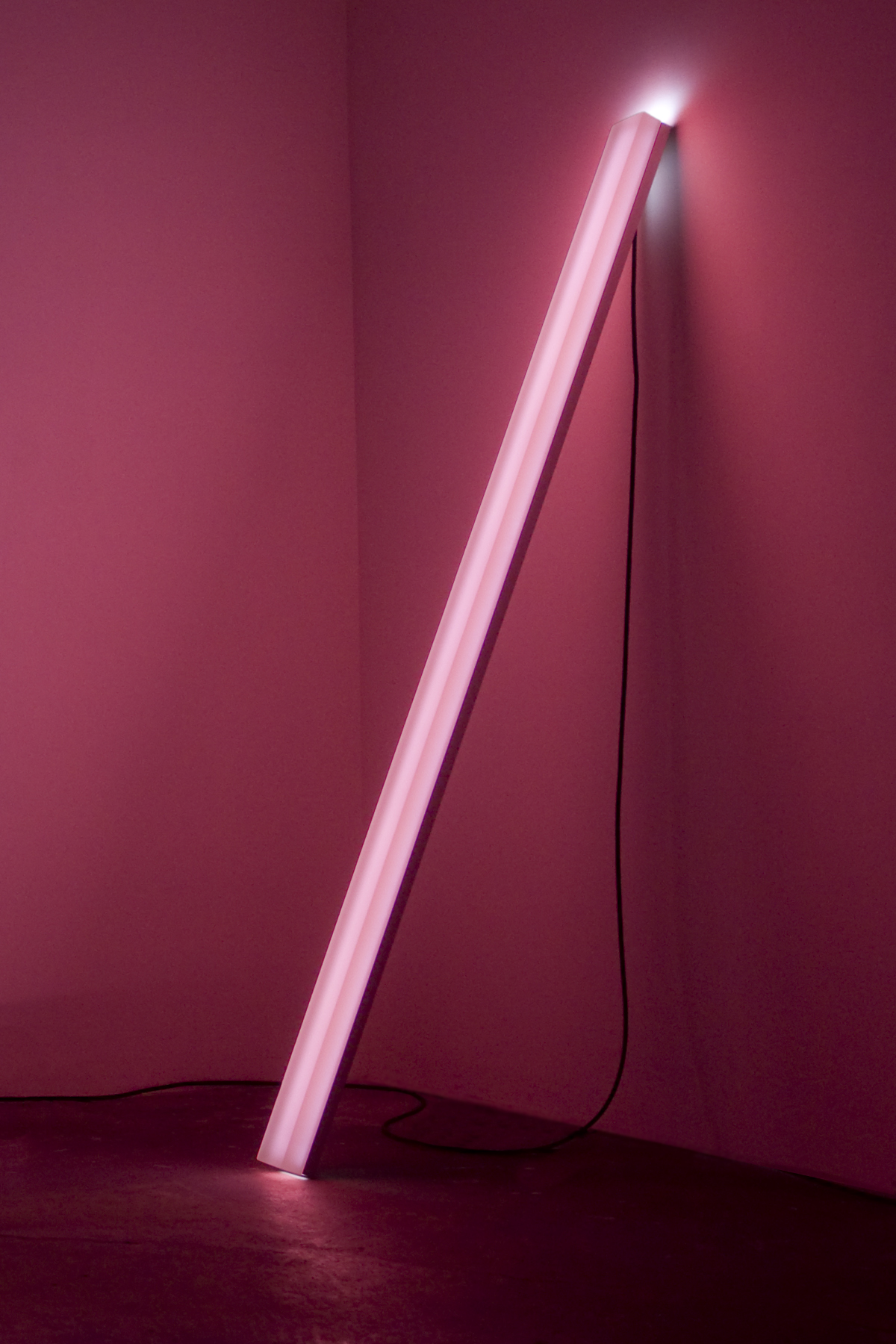

- Spectrosonic – Pink

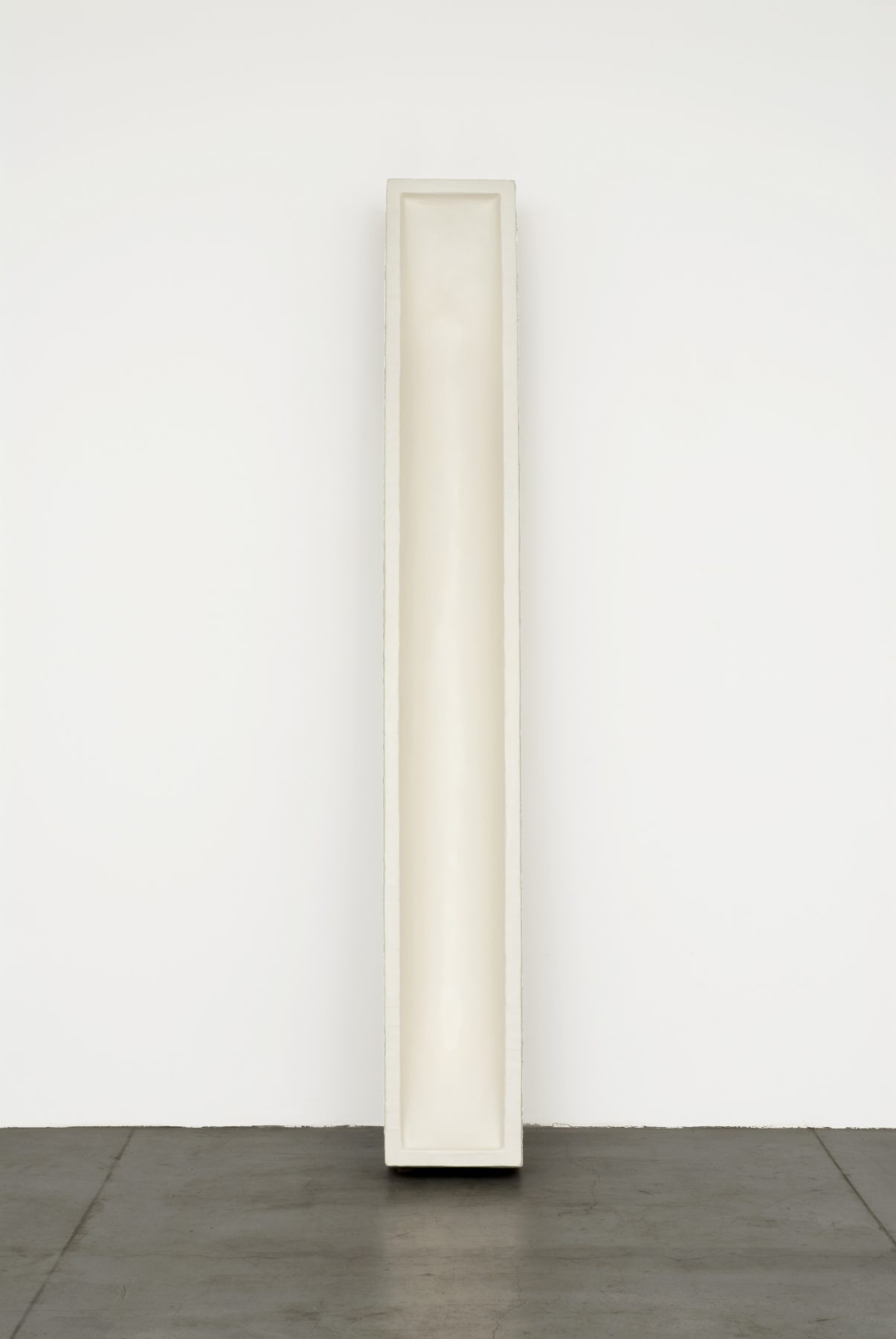

- Light Beam Diptych – White White

- Chromasonic – Blue Green

- Spectrosonic — Yellow Pink

- Spectrosonic — Pink

- Peak Light Extractor — Grey/Yellow

- Peak Light Extractor – Blue/Violet

- Peak Light Extractor — Pink/Yellow

-

2009

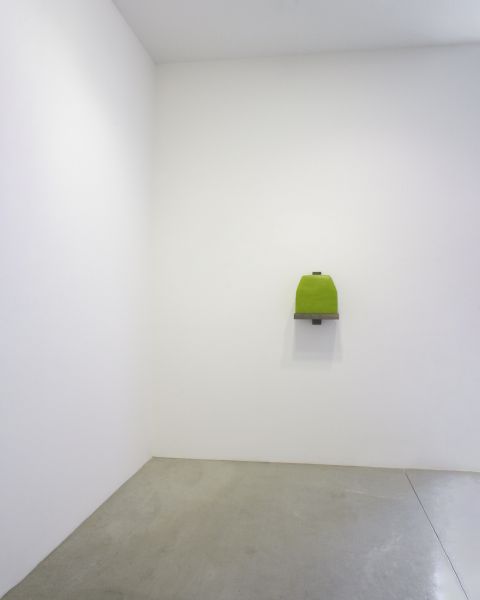

Exposed Icons -

2017

Resonant Disk — Edition

- Resonant 01-03

- Resonant 04-06

- Resonant 07-09

- Resonant 10-12

-

2003–2011

Light Reactive Organic Sculpture

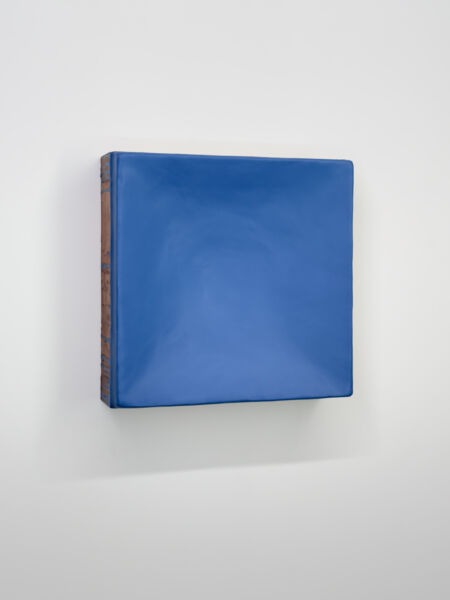

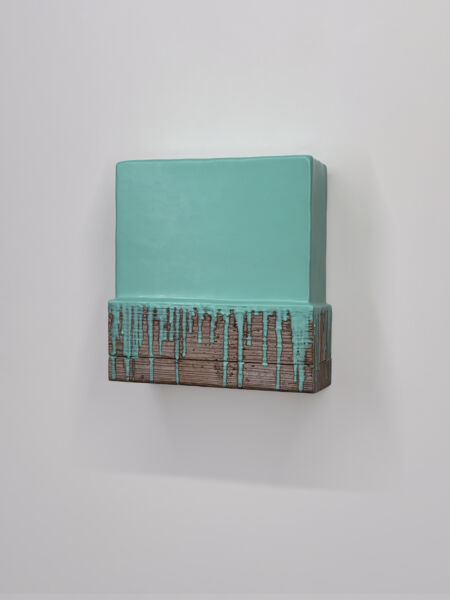

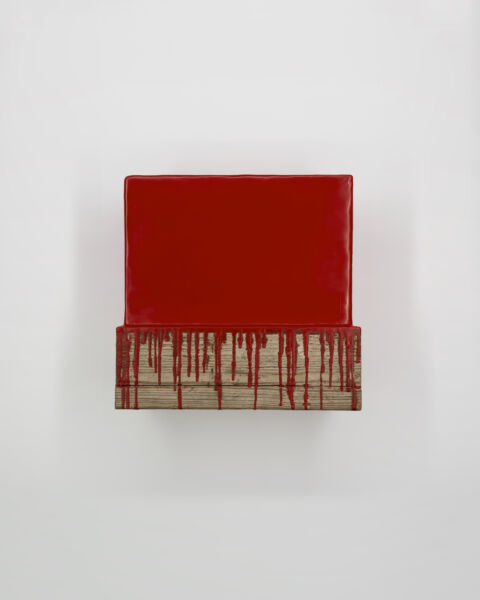

- Colorvoid (Facebox) — Red

- Light Object — Yellow

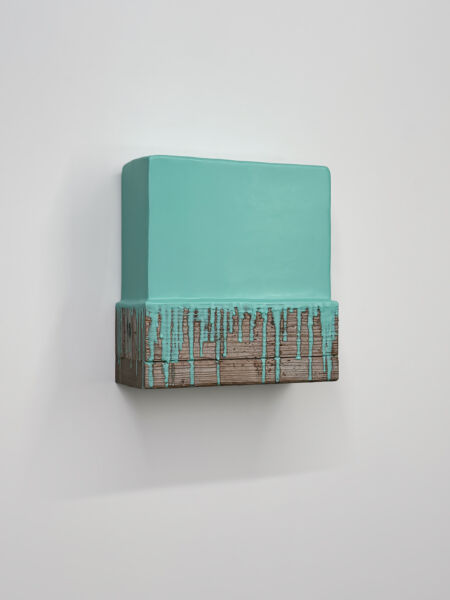

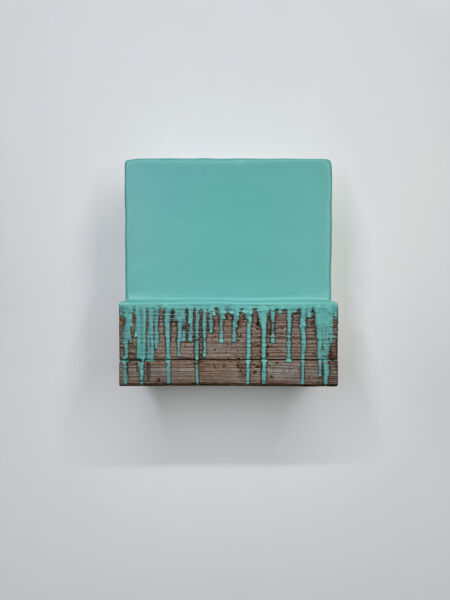

- Dripbox — Yellow White

- Diptych — Carbon Black

- Dripbox — Quinacridone Gold

- Dripbox — Titanium White

- Diptych — Yellow Green

- Triptych — Titanium White

- Colorvoid (Trough) — Titanium White

- Dripbox — Dioxazine Violet

- Colorvoid (Trough) — Mars Red Orange

- Dripbox — Cadmium Yellow Deep

- Triptych — Cadmium Green

- Colorvoid (Trough) — Cadmium Yellow

- Dripbox — Graphite

Exhibitions

-

2024

PDX Contemporary ╱ (in)finitetest

-

2018

Lévy Gorvy; Sensing Singularity

- Lévy Gorvy; Sensing Singularity — Resonant

- Lévy Gorvy; Sensing Singularity — Metaspace V3

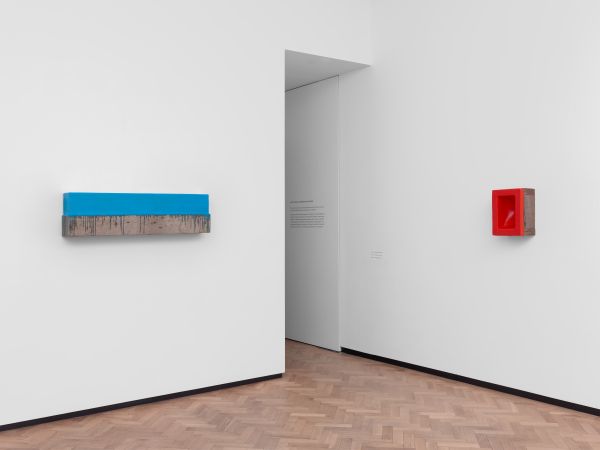

- Lévy Gorvy; Sensing Singularity — Light Reactive Organic Sculpture

-

2018

Museum Voorlinden; Rhapsody in Bluetest

-

2017

PDX Contemporary; Resonancetest

-

2013

Nye + Brown; Off and Ontest

-

2005

Ludwig Museum; Personal Structurestest

-

2004

Steven Haller Gallery; Johannes Girardonitest

Art and Architecture

Chromasonic

-

2022

Chromasonic — Field Studytest

-

2021

Chromasonic — Satellite Onetest

-

2019

Chromasonic — Fluid Statestest

Texts / Catalogs / Books

-

2024

Art & Architecture -

2024

Studio Harriet & Johannes Girardoni -

2024

Metaspaces -

2022

The World of Chromasonic is Built of Pure Light and Sound -

2019

Spectral Bridge House: Blending Art+Architecture -

2017

Resonance; Richard Speer -

2014

Off and On; Sculpture Magazine -

2013

In Conversation with Johannes Girardoni; Jeff Simpson -

2013

Off and On; Exhibition Catalog -

2010

Seeing, Outside Our Selves; Johannes Girardoni -

2006

Personal Structures; Sculpture Magazine -

2005

Ludwig Museum Symposium; Johannes Girardoni

- 2025

-

Spectrosonic – Pink

test

-

Spectrosonic – Pink

- 2024

- 2023

-

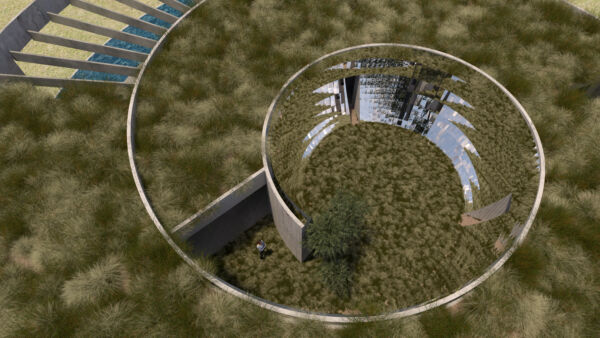

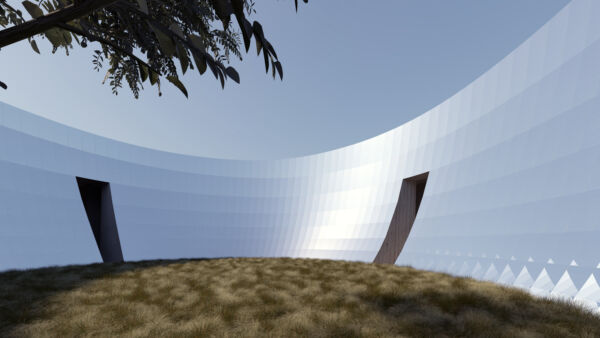

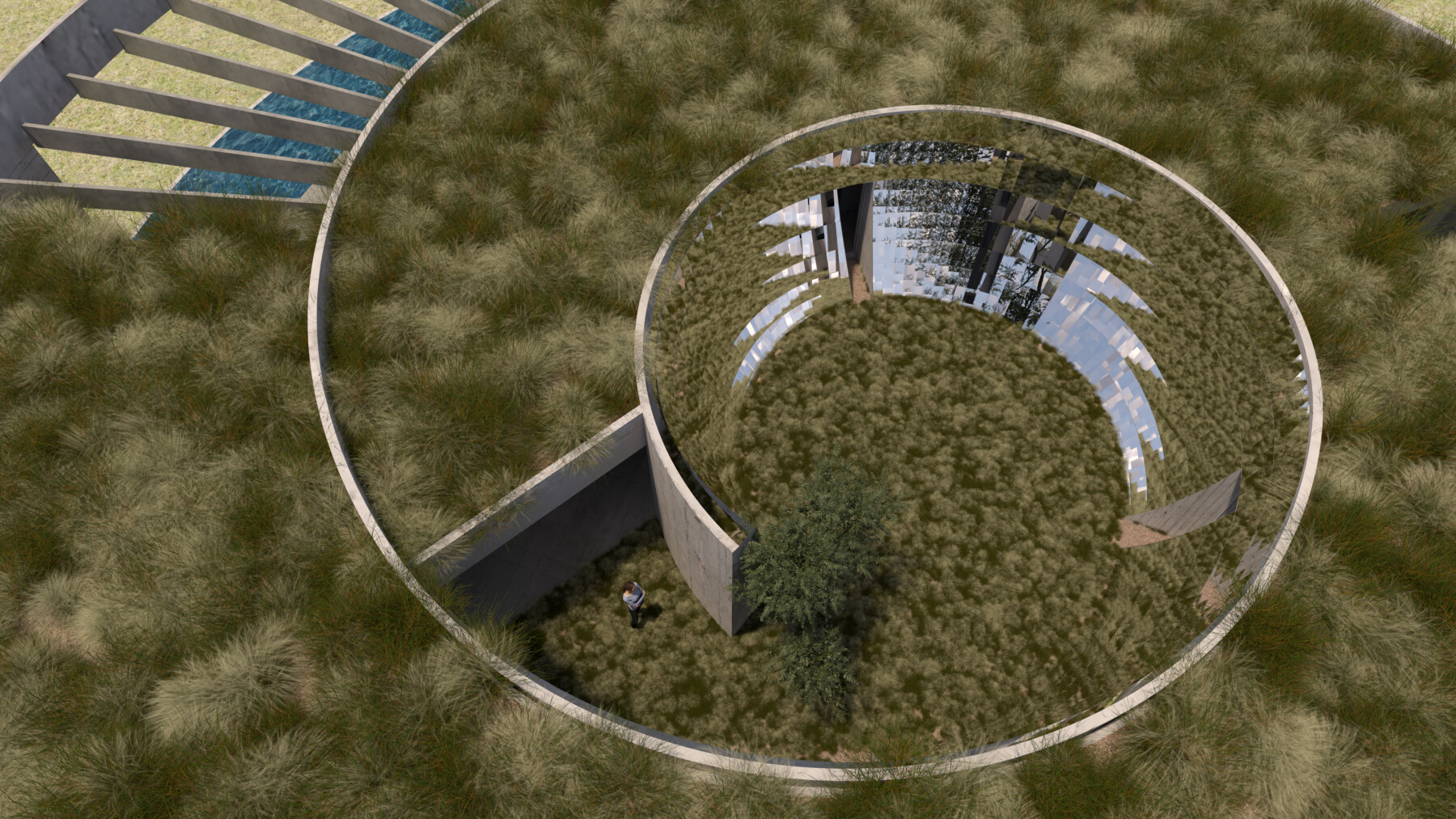

Vortex House

test

-

Vortex House

- 2022

- 2021

- 2019

- 2018

-

Lévy Gorvy; Sensing Singularity — Resonant

test

-

Lévy Gorvy; Sensing Singularity — Metaspace V3

test

-

Lévy Gorvy; Sensing Singularity — Light Reactive Organic Sculpture

test

-

Museum Voorlinden; Rhapsody in Blue

test

-

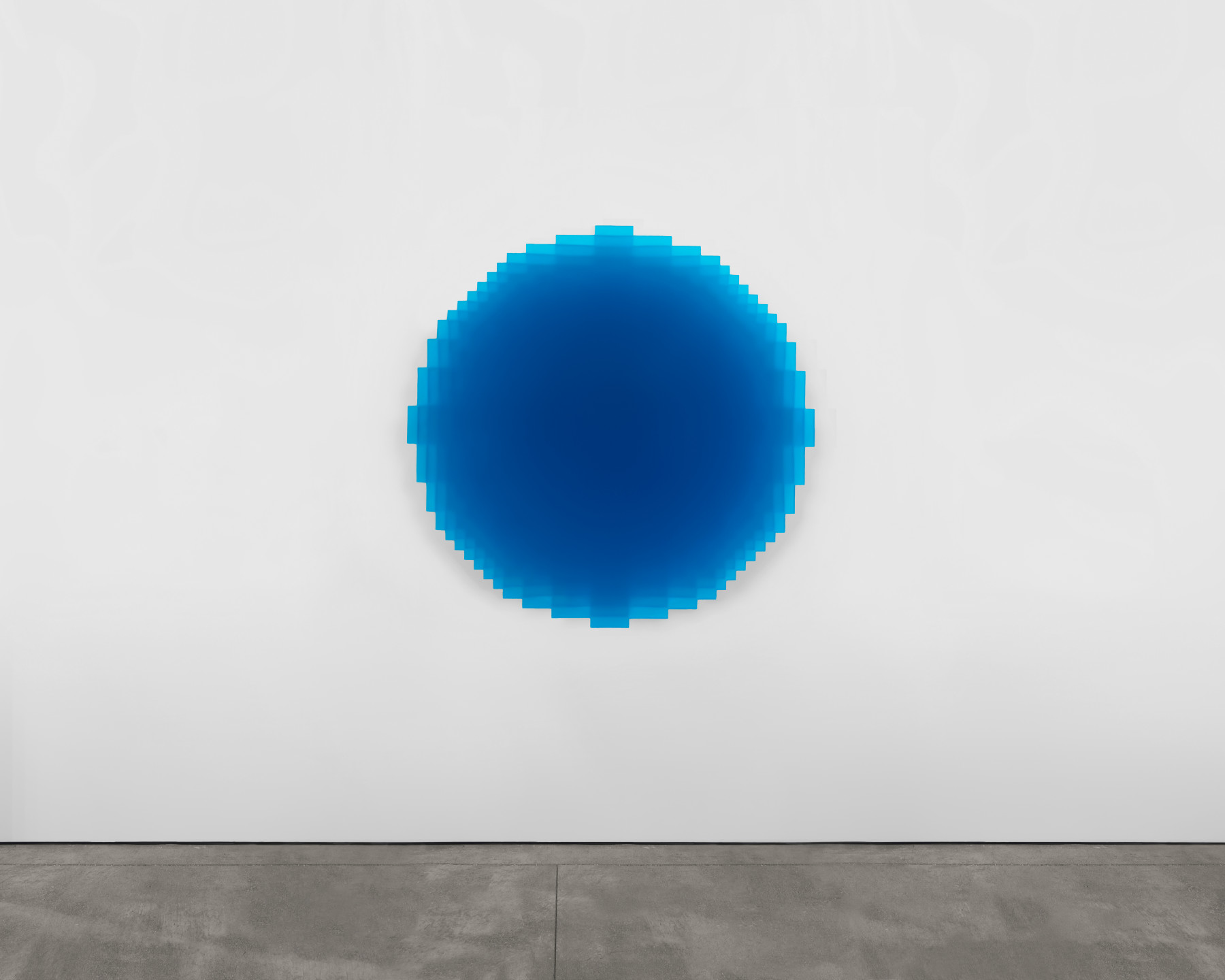

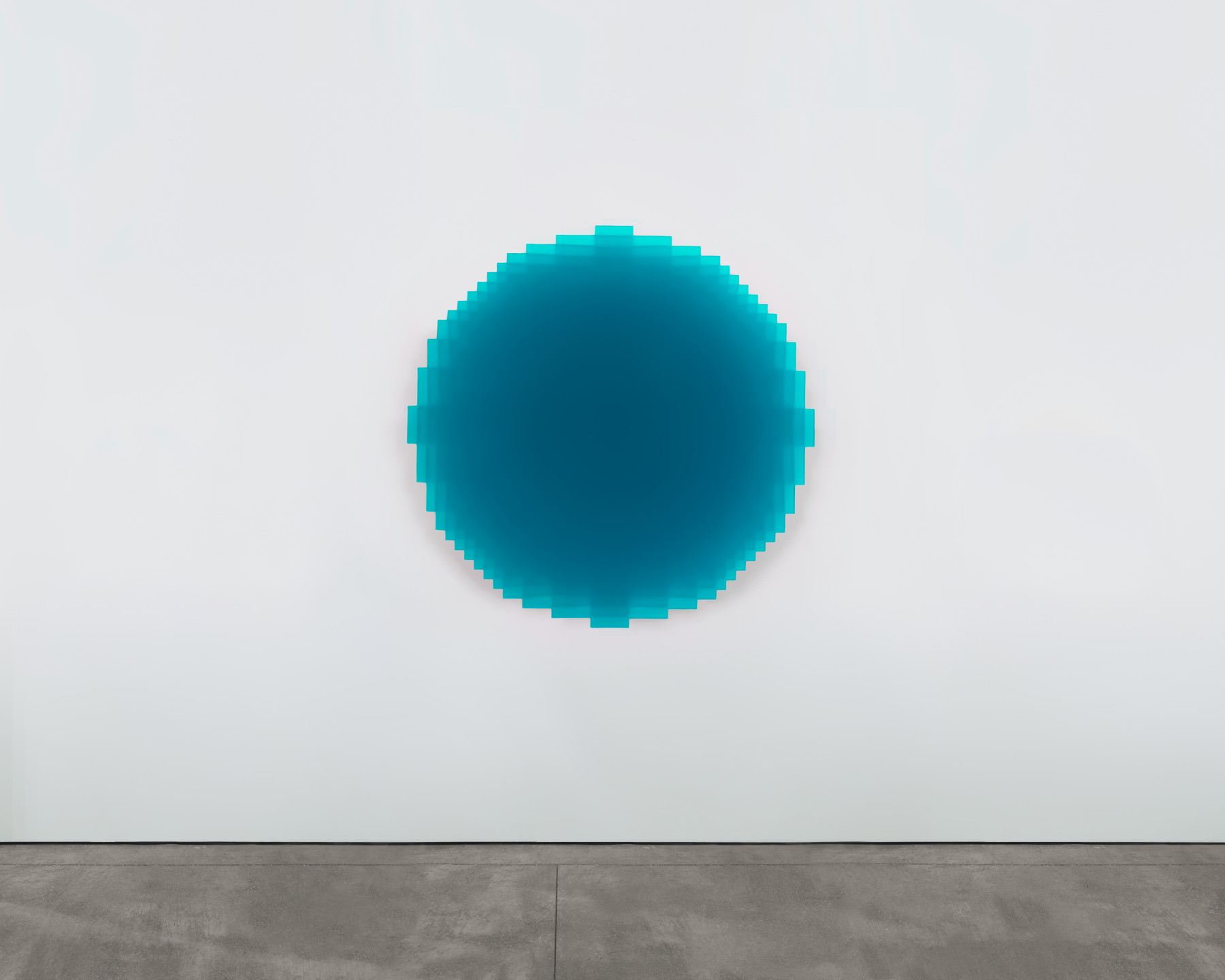

Resonant Disk – Blue Green

test

-

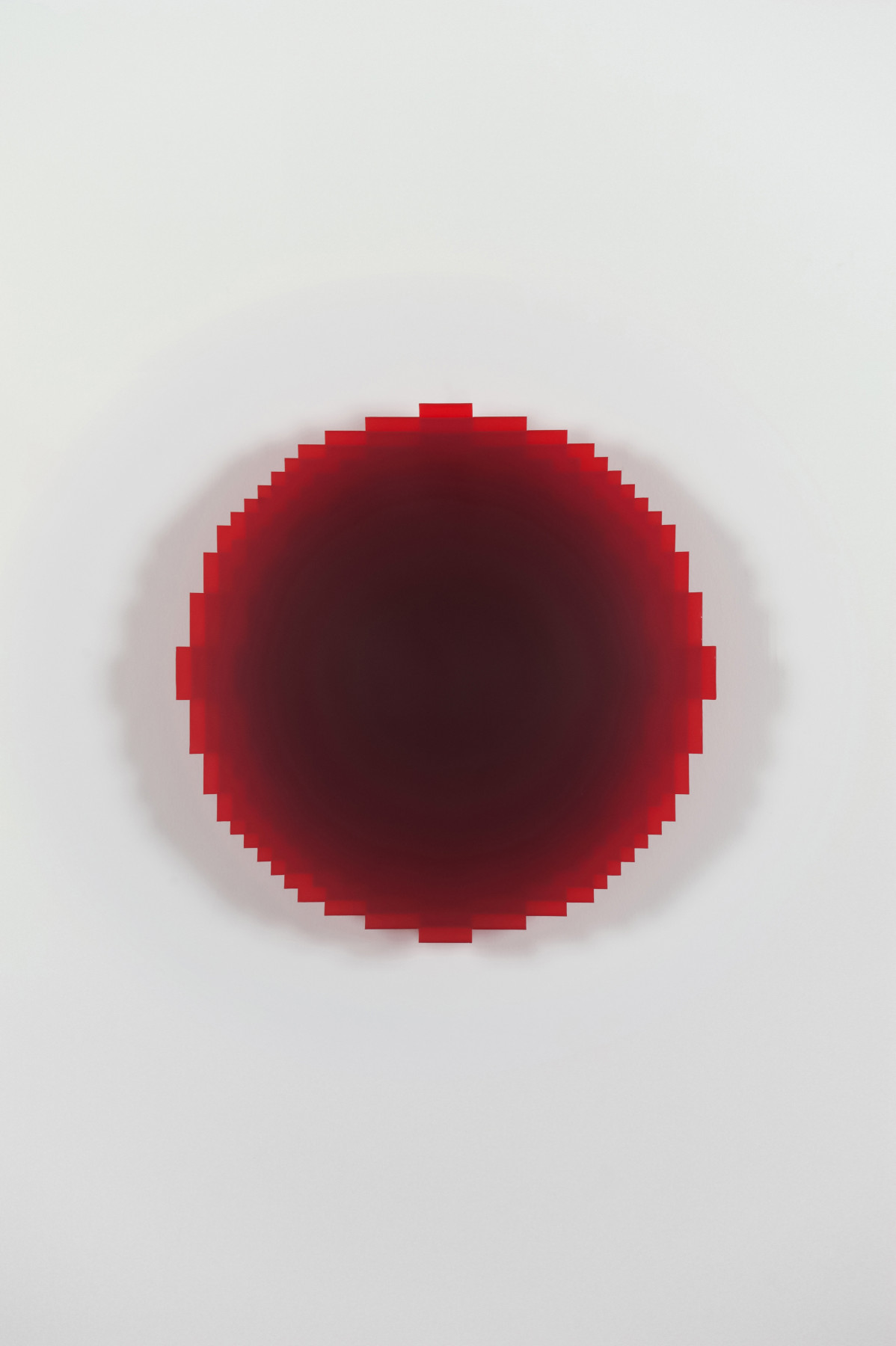

Resonant Disk – Red Violet

test

-

Resonant Disk — Yellow Blue

test

-

Lévy Gorvy; Sensing Singularity — Resonant

- 2017

-

Resonance

test

-

Resonance; Richard Speer

-

PDX Contemporary; Resonance

test

-

Resonant 01-03

test

-

Resonant 04-06

test

-

Resonant 07-09

test

-

Resonant 10-12

test

-

Resonance

- 2014

- 2013

-

In Conversation with Johannes Girardoni; Jeff Simpson

-

Off and On; Exhibition Catalog

-

Metaspace V2 (exterior)

test

-

Metaspace V2 (interior)

test

-

Metaspace V2 (projection)

test

-

Nye + Brown; Off and On

test

-

Spectrosonic — Yellow Pink

test

-

Spectrosonic — Pink

test

-

Peak Light Extractor — Grey/Yellow

test

-

Chromasonic Field — Blue / Green

test

-

In Conversation with Johannes Girardoni; Jeff Simpson

- 2012

- 2011

- 2010

- 2009

- 2008

- 2007

- 2006

- 2005

- 2004

- 2003

- 1995